One of the notable features provided by the Elixir language is the way it handles concurrency, and how this is beneficial on a daily basis and adds value to the final software. One of the things that come up when learning about concurrency in Elixir is an acronym we hear a lot, called OTP.

OTP

The acronym stands for Open Telecom Platform, but it isn’t used just for telecom nowadays. In the book Designing for Scalability with Erlang/OTP, written by authors Francesco Cesarini and Steve Vinoski, they define OTP as three key components that interact with each other: the first one is Erlang itself, the second is a set of libraries available with the virtual machine and the third is a set of system design principles.

Therefore, you may have heard the expression “OTP compliant”, which means that the application follows the system design principles established by Erlang/OTP.

One of the items in this set of principles is based on using process architecture to solve your application problems.

Processes

When we talk about process in Elixir, we are referring to the Erlang virtual machine processes, not the operating system processes. BEAM (Erlang virtual machine) processes are much lighter and cheaper than operating system processes and run in all available machine’s cores, and because they are lighter, on average 2k, we can create thousands of them in our application.

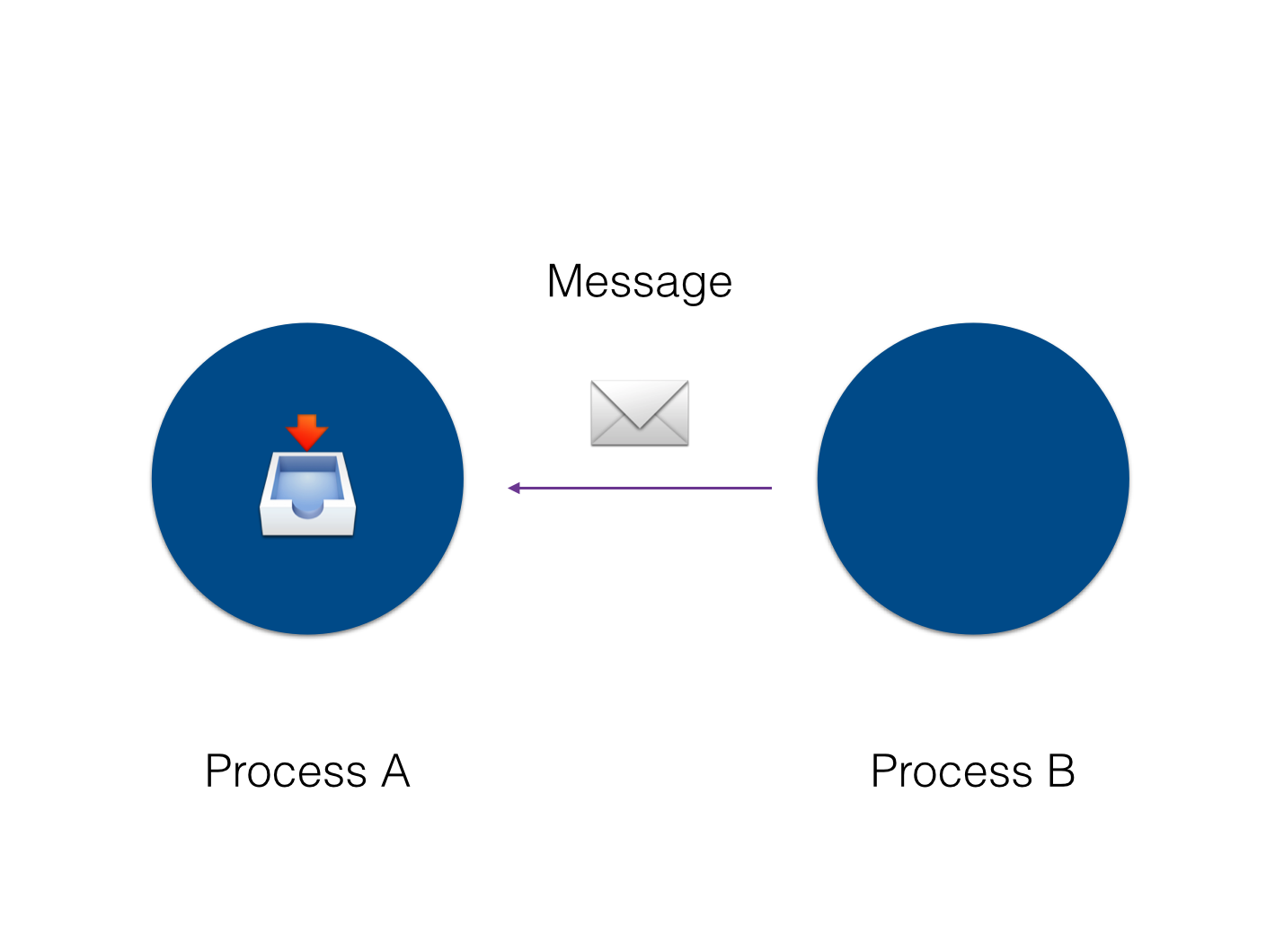

They are isolated from each other and communicate through messages, thus helping us divide the workload and run concurrent things.

Elixir being a functional language, one of its features is immutability, which helps us to express an explicit state. Hence, when we separate our code into independent tasks that can run concurrently, we don’t have to worry about controlling its state using complex mechanisms to ensure this, things like mutex and threads usage are no longer needed.

How do processes work in Elixir?

It is very common to associate processes and the message exchange between them with the actor model for concurrency. This happens because each process in Elixir is independent and completely isolated from one another. A process can save states, but this is not shared, and the only way to share something among processes is by sending messages.

Each process has a mailbox that, as the name suggests, is responsible for receiving messages from other processes. It is also worth mentioning that when we send a message, everything happens asynchronously, so we don’t block processing waiting for a response.

One way to think about this is to imagine processes like cell phones that use SMSs to exchange information, as each cell phone has a place to store those messages until they are handled, and this happens in an independent and isolated manner.

It’s worth mentioning that we can also link a process to another. This is important because, based on this concept, we can identify faults and act to deal with them.

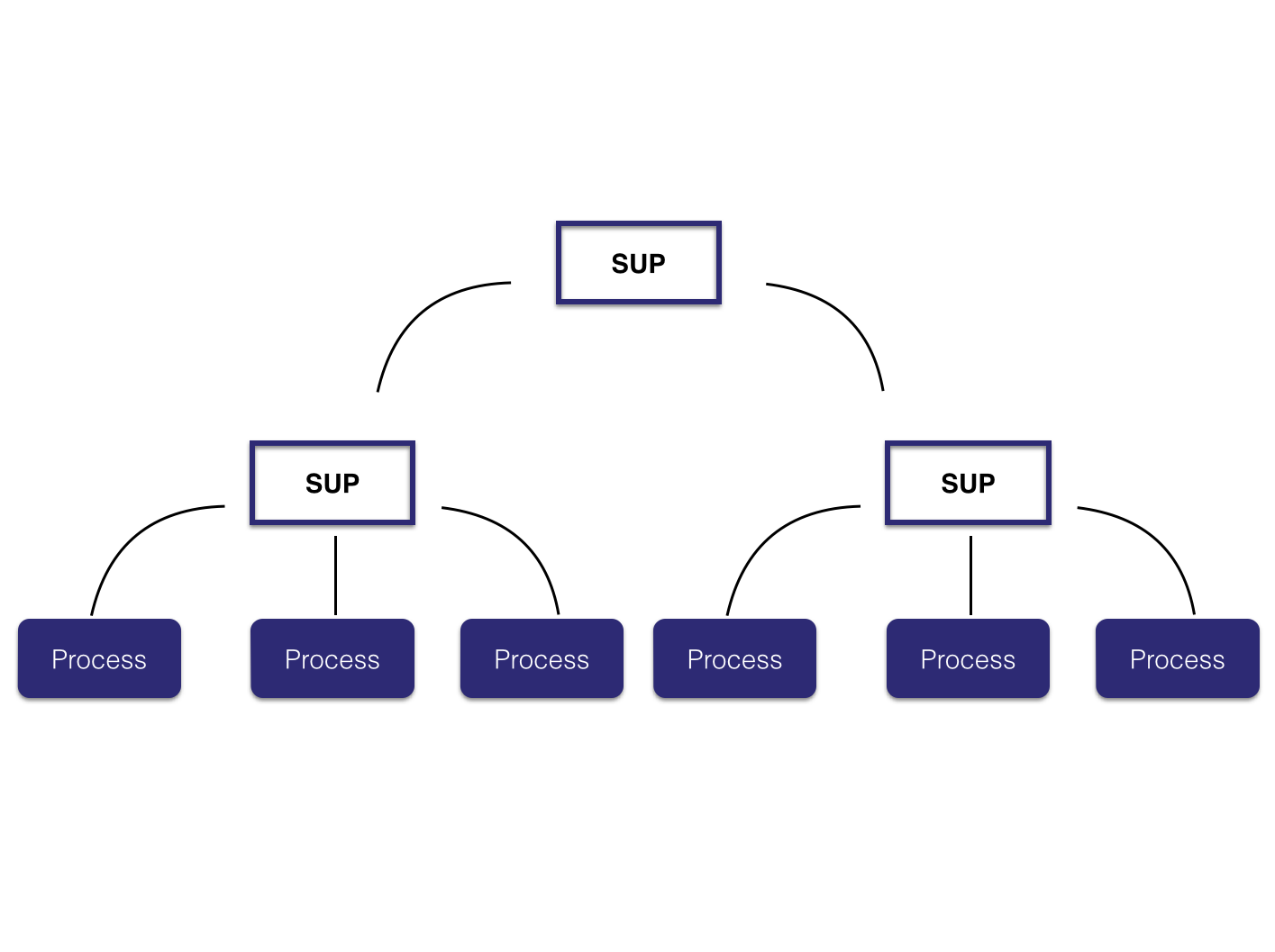

When we have processes that monitor other processes, we name them Supervisor. We can have several of these in our application and when we have more than one Supervisor monitoring processes we call this a Supervision Tree.

This is very important as it enables us to provide fault tolerance because when we have a problem with our code, the last thing we want is that it affects the end-user. By monitoring processes, we can identify when something unexpected happens and work on it, terminating the process with an issue and restarting it, thus, the process returns to its initial state, giving us time to act and solve the issue that caused the error.

How does this work for concurrency?

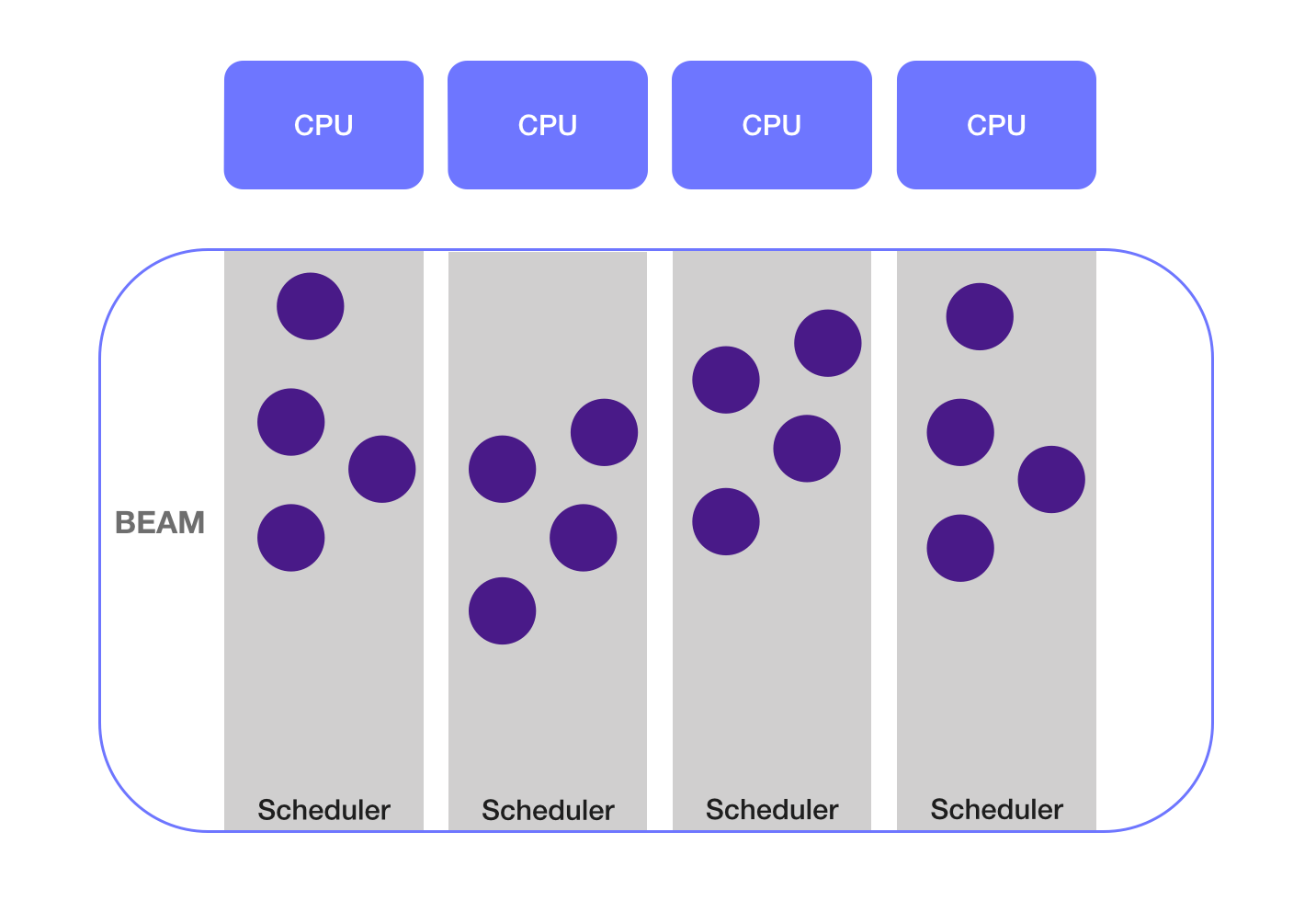

When BEAM starts, it also starts a thread named Scheduler that is responsible for running each process concurrently on the CPU.

To take full advantage of the hardware, BEAM starts a Scheduler for each available core, that is, a computer that has four cores will have four schedulers, each running several processes concurrently.

Processes are the foundation for the concurrency model we use in Elixir. Many of the features we need when using processes have some abstraction to help us, therefore, we don’t have to worry about the implementation details of more primitive functions such as spawn, send, and receive.

When we use these primitive functions, we need to worry about several additional error-prone details to achieve our goal and ensure our code is OTP compliant. Usually, developers don’t use these functions, instead, they use abstractions such as Task, GenServer, and Agent. But that is a topic for another post.